PREVIOUS: JAPAN-KAMAKURA

JAPAN 1890 - 1904

LAFCADIO HEARN IN MATSUE 1890 - 1891

To find the various places connected with Hearn, download the Google Earth program from the internet and then install the

GE Lafcadio Hearn Post

Honoring a Westerner in Japan,

New York Times, 20 February 2007

As snow silently fell on the miniature garden outside, Bon Koizumi sat on the same tatami mat floor where, more than a century before, his great-grandfather wrote down some of Japanís best-loved folk tales.

Bon Koizumi, Lafcadio's grandson

Mr. Hearnís descriptions of this medieval city and its ancient tales of gods and ghosts put Matsue on the map in the 1890s. Even now it is a popular tourist destination, thanks to Japanís enduring fascination with Mr. Hearn, who married a local samuraiís daughter, took Japanese citizenship and died in Tokyo in 1904.

In the United States there was Alexis de Tocqueville, a French aristocrat whose descriptions of fledgling American democracy in the early 19th century still resonate today.

For many Japanese, Mr. Hearnís appeal lies in the glimpses he offered of an older, more mystical Japan lost during the countryís hectic plunge into Western-style industrialization and nation building. His books are treasured here as a trove of legends and folk tales that otherwise might have vanished because no Japanese had bothered to record them.

Matsue appears so often in Mr. Hearnís books that most Japanese naturally associate him with the city, even though he cut short his stay here to escape the bitter winters. He spent most of his 14 years in Japan in another provincial city, Kumamoto, and in Tokyo before his death at 54. The 300-member Hearn Society of Matsue invites scholars for conferences and promotes the Hearn legacy with Irish cooking festivals, classes in Gaelic and, this year, its first St. Patrickís Day parade....

Martin Fackler, NY-Times, 2007

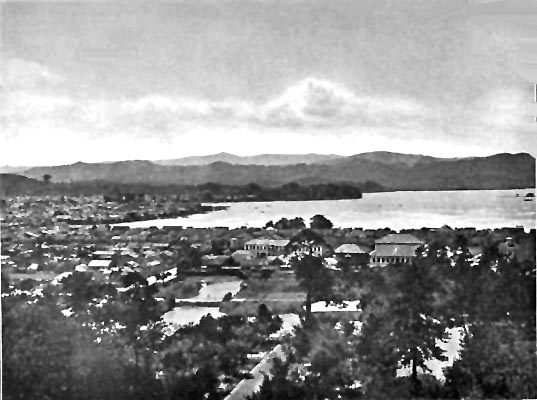

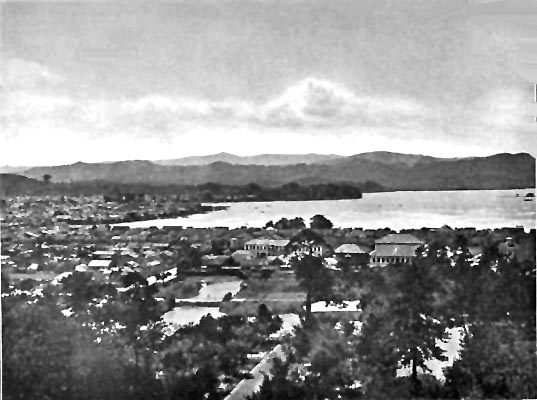

The town of Matsue, 1890

The 15 months Hearn spent in the quaint old city of Matsue

was one of the happiest and intellectually most productive of Hearn's life.

Lafcadio Hearn in a kimono, 1890

Through a fellow teacher at Matsue Middle School a marriage with Setsu Koizumi, the daughter of a local samurai family, was formally arranged.

Hearn and his wife 1891. He adopted her family name: Kazuo Koizumi. When he was made professor at Imperial Tokyo University in 1896 he became a Japanese citizen.

Photos from The Life and Letters of Lacadio Hearn, by Elizabeth Bisland, Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, 1906

Matsue - Hearns new House

Hearn's tiny house in town became too hot in the summer, and he moved to this former residence of a samurai:

.

Matsue Hearn's House. The couple is Hearn and his wife, 1891

"I found it necessary to move to the northern quarter of the city,

into a very quiet street behind the mouldering castle.

My new home is a katchiu-yashiki, the ancient residence

of some samurai of high rank. It is shut off from the

street, or rather roadway, skirting the castle moat by a.

long, high wall coped with tiles. One ascends to the

gateway, which is almost as large as that of a temple

court, by a low broad flight of stone steps.

There exists a very pretty garden, or rather a series of garden spaces, which

surround the dwelling on three sides. Broad verandas

overlook these, and from a certain veranda angle I can

enjoy the sight of two gardens at once."

Photo from The Life and Letters of Lacadio Hearn, by Elizabeth Bisland, Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, 1906

Quotation from Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, p.248

Hearn's Garden.

"In Buddhism all existences are divided into Hijo,

things without desire, such as stones and trees; and Ufa,

things having desire, such as men and animals.

The folk-lore of my little domain relates both to the inanimate

and the animate. In natural order, the Hijo may

be considered first, beginning with a singular shrub near

the entrance of the yashiki, and close to the gate of the

first garden.

Within the front gateway of almost every old samurai

house, and usually near the entrance of the dwelling itself,

there is to be seen a small tree with large and peculiar

leaves. The name of this tree in Izumo is tegashiwa, and

there is one beside my door.

The shape of the

leaves of the tegashiwa somewhat resembles the shape of

a hand. Now, in old days, when the samurai retainer was

obliged to leave his home in order to accompany his

daimyo to Yedo, it was customary, just before his departure,

to set before him a baked tai [a local fish] served up on a

tegashiwa leaf.

After this farewell repast, the leaf upon

which the tai had been served was hung up above the

door as a charm to bring the departed knight safely back

again. This pretty superstition about the leaves of the

tegashiwa had its origin not only in their shape but in

their movement. Stirred by a wind they seemed to beckon, ó

not indeed after our Occidental manner, but in the way

that a Japanese signals to his friend to come, by gently waving

his hand up and down with the palm towards the ground."

Photo Panoramio

Text from Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, p.257

SHINKOKU, THE LAND OF THE GODS

The coast of Izumo-Shinkoku, south-west of Matsui

"Shinkoku is the sacred birth place of

Japan, - ďThe Land of

the Gods;Ē and of all Shinkoku the

most holy ground is Kitzuki..

Hither from the blue Plain of High

Heaven first came the

Earth-makers, Izanagi and Izanami, the

parents of gods and of men; somewhere upon the border of this land was

Izanami buried; and out of this land

into the black realm of the dead did

Izanagi follow after her, and seek in

vain to bring her back again.

And of all legends primeval concerning

the Underworld this story is one of the

weirdest,- more weird even than the

Assyrian legend of the Descent of Ish-

tar.

[Armed] with a letter of introduction from my dear friend Nishida Sentaro, I set out on my first journey to Kitzuki."

Photo and quotation from The Life and Letters of Lacadio Hearn, by Elizabeth Bisland, Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, 1906

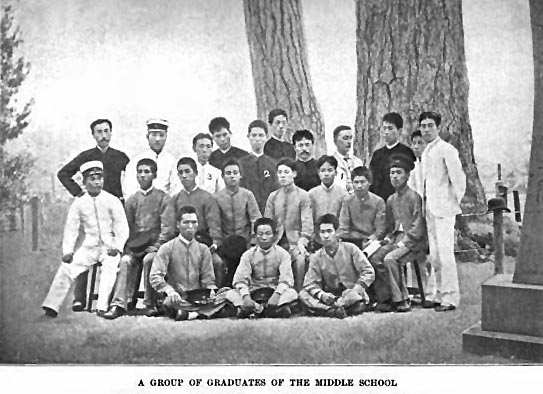

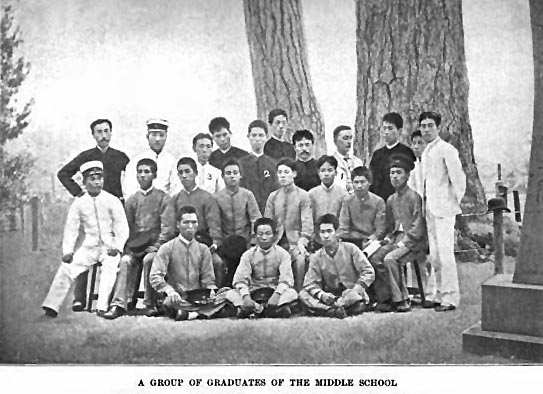

FROM THE DIARY OF AN ENGLISH TEACHER.

MATSUE, September 2, 1890.

The Class of 1890 at Jinjo Chugakko. Hearn is the 4th from the right.

" I am under contract to serve as English teacher in

the Jinjo Chugakko, or Ordinary Middle School. The Jinjo Chugakko is an immense two-story

wooden building in European style, painted a dark

gray-blue. It has accommodations for nearly three

hundred day scholars. It is situated in one corner of

a great square of ground, bounded on two sides by

canals, and on the other two by very quiet streets.

This site is very near the ancient castle.

It is my first day at the schools. Nishida Sentaro,

the Japanese teacher of English, has taken me through

the buildings, introduced me to the Directors, and

to all my future colleagues.

Nishida leads the way to

the Kencho, or Prefectural office, situated in another

foreign-looking edifice across the street.

We enter it, ascend a wide stairway, and enter a

spacious room carpeted in European fashion. One person

is seated at a small round table, and about him are

standing half a dozen others : all are in full Japanese

costume, ceremonial costume, ó splendid silken ha-

kama, or Chinese trousers, silken robes, silken haori

or overdress, marked with their mon or family crests :

rich and dignified attire which makes me ashamed

of my commonplace Western garb. These are officials

of the Kencho, and teachers : the person seated is the

Governor. He rises to greet me, gives me the hand-

grasp of a giant.

Indeed the first impression of him is that of

a man of another race. While I am wondering

whether the old Japanese heroes were cast in a similar

mould, he signs to me to take a seat, and questions

my guide in a mellow basso. There is a charm

in the fluent depth of the voice pleasantly confirming

the idea suggested by the face.

The Governor suggests that I make visits to the celebrated

shrines of Kitzuki, Yaegaki, and Kumano,

and then asks : ó "

Does he know the tradition of the origin of the

clapping of hands before a Shinto shrine ? "

I reply in the negative ; and the Governor says

the tradition is given in a commentary upon the

Kojiki. "

It is in the thirty-second section of the fourteenth

volume, where it is written that Ya-he-Koto-

Shiro-nushi-no-Kami clapped his hands."

I thank the Governor for his kind suggestions and

his citation. After a brief silence I am graciously

dismissed with another genuine hand grasp ; and we

return to the school. "

Photo from The Life and Letters of Lacadio Hearn, by Elizabeth Bisland, Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, 1906

Letter from: Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, p.430

MUST SEE just for relief: An online blog of a Valentine's Day in today's Japanese Middle School (2008).

Akiba Kei (xxlithiumflower)

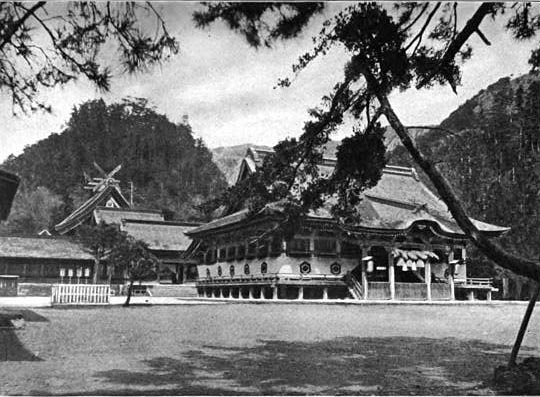

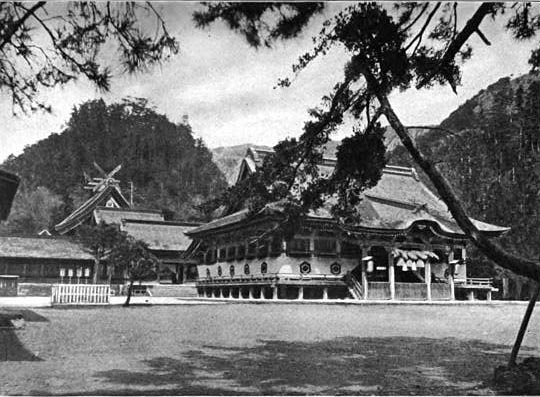

IZUMO TAISHA (Kitzuki)

The Great Hall at Taisha, the oldest Shinto sanctuary in Japan and the birth-place of Shinto rites, mysteries and mythologies which would influence Hearn immensely: "Shinkoku, the Land where the Gods were born."

Hearn visited Taisha, (or as he calls it Kitzuki) during the school vacations in the Summer of 1891 which he spent in the nearby beach town of Kitzuki (now Izumo Taisha).

"Most memorable was his vision of one of the temple girls:

He writes in "Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan":

"Always, through the memory of my first day at Kitzuki,

there will pass the beautiful white apparition of the Miko,

with her perfect passionless face, and strange, gracious,

soundless tread, as of a ghost. Her name signifies "the Pet," or "the Darling of the Gods," - Mi-ko.

Contrary to the custom at the other great Shinto

temples of Japan, such as Ise, the office of miko at Kitzuki

has always been hereditary. At the Kitzuki Oho-yashiro the maiden -priestesses are beautiful girls of between sixteen and nineteen years of age; and sometimes a favourite miko is allowed to continue

to serve the gods even after having been married.

Like the priestesses of Delphi, the miko was in ancient

times also a divineress,- a living oracle, uttering the secrets

of the future when possessed by the god whom she served.

At no temple does the miko now act as sibyl. But there still exists a class of divining-women, who claim to hold communication with

the dead, and to foretell the future, and who call themselves

miko, - practising their profession secretly; for it

has been prohibited by law.

In the various great Shinto shrines of the Empire the sacred

Miko-kagura dance is danced differently. In Kitzuki, it is most ancient

of all.

The origin of this dance is to be found in the Kojiki

legend of the dance of Ame-no-uzume-no-mikoto - she by

whose mirth and song the Sun-goddess was lured from

the cavern into which she had retired, and brought back to illuminate the world. And the suzu - the strange bronze

instrument with its cluster of bells which the miko uses

in her dance - still preserves the form of that bamboo-

spray to which Ame-no-uzume-no-mikoto fastened small

bells with grass, ere beginning her mirthful song."

Photo from The Life and Letters of Lacadio Hearn, by Elizabeth Bisland, Houghton, Mifflin, Boston, 1906

Text from: Lafcadio Hearn, "Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan", Tauchnitz, Leipzig, 1910

HOKI 1890

By the Japanese Sea a few miles north of Matsui

THE FESTIVAL OF THE DEAD

"It is the fifteenth day of the seventh month, - and I

am in Hoki: The three days of the Bon. And on the

sixteenth day, after the shoryobune, the sea is the highway of the dead, who must pass back over its waters to their mysterious

home; and therefore upon that day is it called Hotoke-

umi, - the Buddha-Flood, - the Tide of the Returning

Ghosts. The Ships of Souls, have been launched. And ever upon the night of that sixteenth day, -

whether the sea be calm or tumultuous, - all its surface

shimmers with faint lights gliding out to the open, - the

dim fires of the dead; and there is heard a murmuring

of voices, like the murmur of a city far-off, - the indistinguishable

speech of souls.

The shoryobune

are much more elaborately and expensively constructed on this coast

than in some other parts of Japan; for though made of

straw only, woven over a skeleton framework, they are

charming models of junks, complete in every detail. Some

are between three and four feet long. On their white paper

sail is written the kaimyo or soul-name of the dead.

There is a small water-vessel on board, filled with fresh

water, and an incense-cup; and along the gunwales flutter

little paper banners bearing the mystic manji, which is

the Sanscrit svastika."

Photo Panoramio

Text from: Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, p.301

THE OKI ISLANDS 1890

Hearn joined a local merchant in 1890 on a visit to the Oki Islands, where no Westerner had been before. In local folklore the islands have an almost mythical connotation. They had been a place of exile for several former high-officials:

Already under the Nara period the islands were used as an exile for persons from the mainland. In 1198 Emperor Go-Toba (tenno) was sent to exile to Dogo where he stayed until his death in 1239. Between 1331 and 1333 tenno Go-Daigo was exiled to Nishino-shima

An old steamer takes them there. The mainland rececedes and eventually Nishinoshima Island comes in sight.

Amorgos and the Lesser Cycladic Islands in the Greek Archipelagos, RWFG, November 2005.

Hearn has no conscious memory of the islands of his birth in Greece. Yet his text preternaturally also describes the Greek archipelagos, which is the only seascape that resembles the Japanese Islands, especially in Winter:

"The luminous blankness circling us continued to

remain unflecked for less than an hour. Then out

of the horizon toward which we steamed, a small

gray vagueness began to grow. It lengthened fast,

and seemed a cloud. And a cloud it proved ; but

slowly, beneath it, blue filmy shapes began to define

against the whiteness, and sharpened into a chain of

mountains....

The first impression was almost uncanny. Rising sheer from the flood on

either hand, the tall green silent hills stretched away before us,

changing tint through the summer vapour, to form a fantastic vista of

blue cliffs and peaks and promontories. Above their pale bases of naked rock the mountains sloped up

beneath a sombre wildness of dwarf vegetation. There was absolutely no

sound, except the sound of the steamer's tiny engine--poum-poum, poum!

poum-poum, poum! like the faint tapping of a geisha's drum. ....

Yet these Oriental landscapes possess charms of colour extraordinary,

phantom-colour delicate, elfish, indescribable--created by the wonderful

atmosphere. Vapours enchant the distances, bathing peaks in bewitchments

of blue and grey of a hundred tones, transforming naked cliffs to

amethyst, stretching spectral gauzes across the topazine morning,

magnifying the splendour of noon by effacing the horizon, filling the

evening with smoke of gold, bronzing the waters, banding the sundown with ghostly purple and green of nacre."

From Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, p. 573

NEXT: JAPAN-KUMAMOTO-KYOTO-TOKYO